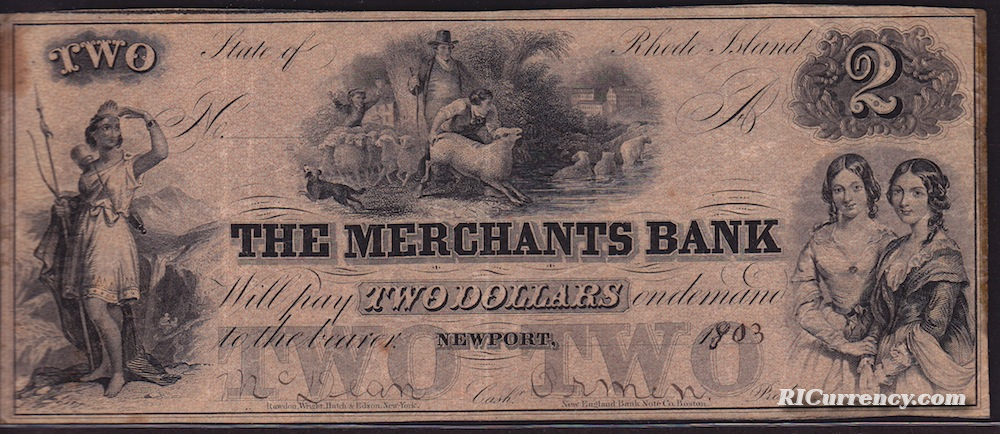

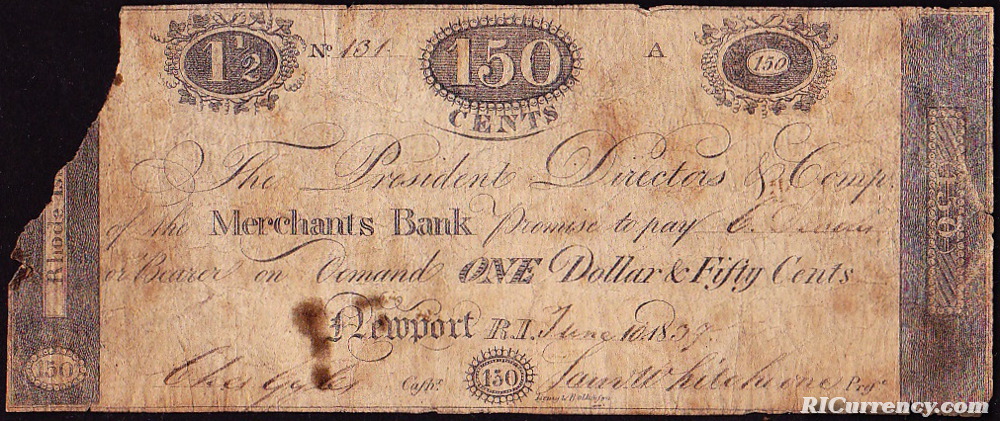

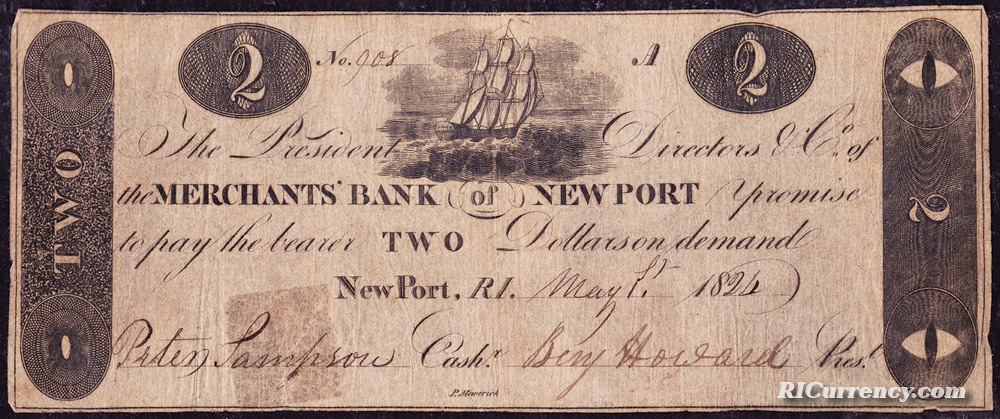

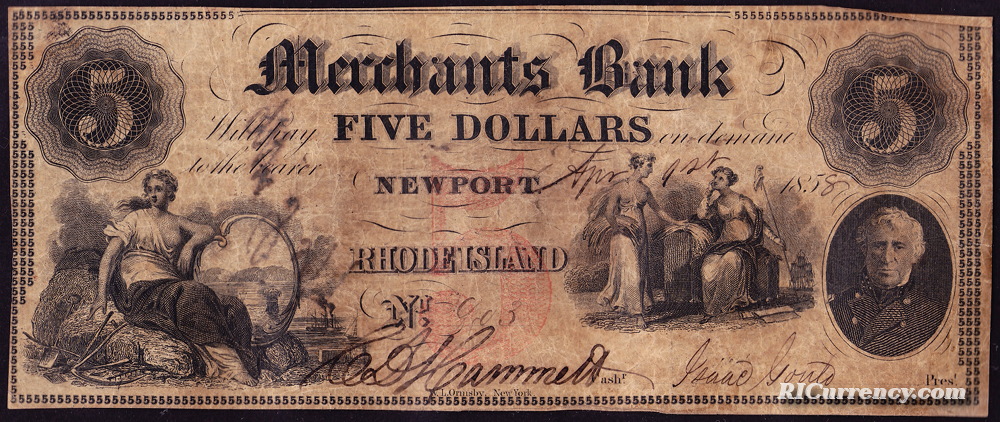

Merchants Bank, Newport

Founded in 1817. Located at 153 Thames Street in 1856. Also based at 223 Thames at one point. It remained a state bank during the first decades of the national banking system. At the end of its life, it was one of only six state banks left in Rhode Island.

The Merchants Bank failed in 1902, though rumblings of its precarious financial nature circulated in the business community of Rhode Island far in advance. On June 23rd of that year, the Manufacturers and Farmers Journal reported on a suicide attempt by Anthony S. Sherman, the bank’s cashier. He took a vial of laudanum and then shot himself in the head (he died several days later). The act caused quite a panic among the bank’s depositors.

Sherman had been a respected member of Newport society and his institution was often referred to as simply, “Mr. Sherman’s Bank.” He had served as treasurer of the Wickford Railroad Line, and had previously been vice president of the Madison Square National Bank of New York. His father, William B. Sherman, was a prior president of the Merchants Bank.

In the aftermath of the suicide, investigators reported that since the institution never joined the national banking system and operated under its original 1817 charter, stockholders were not financially liable for the failure. In fact, one person claimed that the bank hadn’t held a shareholders’ meeting for many years. While many local businesses had been avoiding the bank after the Clearing House Bank of Newport refused to honor its paper, the people most affected appear to have been Newport’s summer residents and, as the article mentioned above notes, its female depositors.

By July 1, 1902, a commission appointed by Rhode Island’s Governor Kimball found that the bank had a shortage of $326,000 and only $10,000 in assets. The cause of the bank’s failure, according to a July 3, 1902 article in the Manufacturers and Farmers Journal, was cashier Sherman’s poor financial bets and irregular bookkeeping:

“His losses were, it is generally considered, due to extensive speculation in regular stocks and bucket shops, and his methods of obtaining money for the purpose were of an extremely varied nature. Deposits would be entered on pass books without appearing on the books of the bank, amounts would be deducted from the balances due depositors, loans were secured without sufficient security, certificates of deposit and certified checks were outstanding without any assets with which to pay them, and some notes were handled in a very peculiar manner.”

The Merchants Bank Building at 223 Thames Street. (Source: One hundred years of the Savings Bank of Newport,

Walton Advertising and Printing Co., Boston, Mass., 1919.)

Bank check from August 2, 1899.